Endemic Species in Seychelles and How They Support Island Habitat Restoration

The Seychelles is internationally recognised as a global hotspot for endemic biodiversity, with a high proportion of its plants and animals found nowhere else on Earth. This exceptional level of endemism is the result of long geographic isolation, island-scale evolution, and highly specific habitat conditions. While this uniqueness gives the Seychelles significant global conservation value, it also creates heightened vulnerability, particularly on small islands where ecological systems are tightly interconnected (IUCN, 2022).

Protecting endemic species in the Seychelles therefore depends on more than species-specific interventions. It requires long-term, science-led habitat restoration and consistent biodiversity monitoring at an island scale. On small islands, changes to vegetation structure, freshwater availability, or soil stability can quickly affect multiple species and ecological processes, increasing the risk of cascading ecosystem degradation (IPBES, 2019).

Wildlife ACT supports endemic species conservation in the Seychelles through its long-term involvement on North Island, where it works alongside the island’s Environmental Team within the award-winning Noah’s Ark Project. This whole-island restoration initiative focuses on restoring ecological integrity across terrestrial habitats, wetlands, and coastal systems, creating the conditions necessary for endemic species persistence and ecosystem recovery over time (North Island, 2025).

On North Island, endemic species such as the Aldabra Giant Tortoise, Seychelles White-eye, and Black Mud Terrapin are monitored within restored habitats to understand ecosystem function, habitat condition, and long-term resilience. Wildlife ACT contributes to this work through its Seychelles Marine and Coastal Conservation programme by strengthening monitoring continuity and ethical conservation support alongside professional conservation teams (Wildlife ACT, 2024).

What Makes the Seychelles a Global Hotspot for Endemic Species

The Seychelles is recognised as one of the world’s most significant centres of island endemism due to its long geographic isolation and complex geological history. Located in the western Indian Ocean, the archipelago has remained isolated from continental landmasses for millions of years. This isolation has allowed species to evolve independently, resulting in high levels of endemism across plants, reptiles, birds, and invertebrates (IUCN, 2022).

Island ecosystems such as those in the Seychelles are characterised by relatively simple food webs and a high degree of ecological specialisation. Many endemic species have evolved to occupy narrow ecological niches, relying on specific habitat conditions, vegetation structures, or resource availability. While this specialisation contributes to biodiversity uniqueness, it also increases vulnerability to environmental change, as endemic species often have limited capacity to adapt or relocate when conditions deteriorate (IPBES, 2019).

The Seychelles supports endemic species including the Aldabra Giant Tortoise, Seychelles White-eye, Seychelles Blue Pigeon, Seychelles Kestrel, and several endemic reptile species such as geckos and skinks. These species are integral to ecosystem function and serve as indicators of habitat condition and ecological integrity across the islands. Their continued presence reflects the health of the systems that support them, from forest and wetland habitats to coastal zones.

Island endemism is closely linked to habitat stability. When habitats are altered through vegetation loss, invasive species, or changes in freshwater availability, endemic species are often the first to be affected. In the Seychelles, historical land use and introduced species have altered habitat structure on several islands, increasing the need for targeted restoration and long-term ecological management (IUCN, 2022).

Understanding the Seychelles as a global hotspot for endemic species therefore requires recognising both its biological value and its fragility. Conservation efforts must address ecosystem function at an island scale, rather than focusing solely on individual species. On North Island, this understanding underpins the development of whole-island restoration and monitoring frameworks designed to protect endemic biodiversity over the long term.

Wildlife ACT supports this approach by contributing to biodiversity monitoring on North Island, helping to build the long-term datasets needed to understand how endemic species respond to habitat restoration within the island’s evolving ecological context (Wildlife ACT, 2024).

Download your North Island Species Checklist below:

The Ecological History of North Island Seychelles and Why Habitat Restoration Was Needed

North Island Seychelles has undergone significant ecological change over time, shaped by both natural processes and human influence. Prior to disturbance, the island supported native forest, coastal vegetation, and wetland systems that evolved in close association with endemic species. These habitats provided structural complexity, freshwater regulation, and ecological connectivity across the island, supporting a range of terrestrial and freshwater species adapted to island conditions (North Island, 2025).

Following human settlement, land use change and the introduction of non-native species altered the composition and function of North Island’s ecosystems. Invasive plant species displaced native vegetation, reducing habitat quality and altering soil structure. Introduced animals further affected breeding success and habitat availability for endemic fauna. Over time, these pressures simplified habitat structure and disrupted ecological processes that had evolved over millennia (North Island, 2025; IUCN, 2022).

By the late twentieth century, much of North Island’s original vegetation had been degraded or replaced. The loss of native plant communities reduced soil stability and affected freshwater retention, increasing vulnerability to erosion and altering wetland function. These changes had cascading effects across the island ecosystem, influencing habitat suitability for endemic species and reducing overall ecological resilience (IPBES, 2019).

The need for large-scale habitat restoration on North Island emerged from this history of degradation. Conservation planning recognised that protecting individual species would be insufficient without addressing the underlying drivers of ecosystem decline. This led to the development of a whole-island restoration approach focused on restoring ecological processes rather than applying short-term or isolated interventions.

Habitat restoration under the Noah’s Ark Project has involved the systematic removal of invasive species, rehabilitation of native vegetation communities, and restoration of wetland systems. These actions aim to rebuild habitat structure and ecological function across terrestrial and freshwater environments, creating the conditions necessary for endemic species persistence over time (North Island, 2025).

As restoration progressed, some species were actively reintroduced through carefully managed conservation programmes, while others returned naturally as habitat conditions improved. This combination of species reintroduction and natural recolonisation reflects a precautionary, evidence-based approach to island restoration, where interventions are guided by ecological need and supported by long-term monitoring rather than short-term outcomes.

Understanding this ecological history is essential for interpreting current conservation efforts on North Island. It explains why habitat restoration remains a long-term priority and why endemic species monitoring focuses on gradual trends rather than immediate results. Wildlife ACT supports this long-term monitoring on North Island by contributing to consistent data collection within the award-winning Noah’s Ark Project, helping to track how restored habitats support endemic species over time (Wildlife ACT, 2024).

Why Endemic Species Are Critical to Ecosystem Stability on Small Islands

Endemic species are critical to ecosystem stability on small islands because they often perform ecological functions that are highly specific to local conditions. Through long periods of isolation, these species have evolved in close association with island habitats, climate patterns, and resource availability. As a result, their roles within ecosystems are often specialised and cannot easily be replaced if populations decline or disappear (IPBES, 2019).

Island ecosystems typically have simplified food webs and limited functional redundancy. This means that when an endemic species is lost, there are often few or no other species capable of fulfilling the same ecological role. The removal of a single species can therefore disrupt multiple ecological processes, such as seed dispersal, vegetation regulation, nutrient cycling, or trophic balance, increasing vulnerability to further disturbance (IUCN, 2022).

In the Seychelles, endemic species contribute to ecosystem stability across terrestrial, freshwater, and coastal environments. Endemic birds influence vegetation dynamics through seed dispersal and habitat use. Endemic reptiles interact with soil and vegetation systems, while freshwater species contribute to wetland function and ecological connectivity. Together, these interactions help maintain the structure and function of island ecosystems over time.

The stability of these systems is particularly important in the context of environmental change. Small islands are highly exposed to climate variability, extreme weather events, and sea level rise. Ecosystems that retain their functional integrity are better able to absorb disturbance and recover over time, whereas systems that have lost key species are more likely to experience rapid degradation (IPBES, 2019).

On North Island Seychelles, the protection of endemic species is therefore closely linked to habitat restoration and long-term ecosystem management. Monitoring endemic species provides insight into how restored habitats are functioning and whether ecological processes are being maintained as environmental conditions change. Rather than focusing solely on population size, conservation teams observe species presence, habitat association, and behavioural patterns as indicators of ecosystem stability.

Wildlife ACT supports this approach on North Island by contributing to long-term endemic species monitoring within the award-winning Noah’s Ark Project. Through consistent data collection and field presence, Wildlife ACT helps strengthen understanding of how endemic species contribute to ecosystem stability in a restored island environment over time (Wildlife ACT, 2024; North Island, 2025).

The Award-Winning Noah’s Ark Project on North Island Seychelles

The conservation framework that underpins endemic species protection on North Island Seychelles is the Noah’s Ark Project, a long-term, whole-island habitat restoration initiative. The project was developed in response to extensive historical habitat degradation and is designed to restore ecological integrity across terrestrial, freshwater, and coastal environments as an interconnected system rather than as isolated habitats (North Island, 2025).

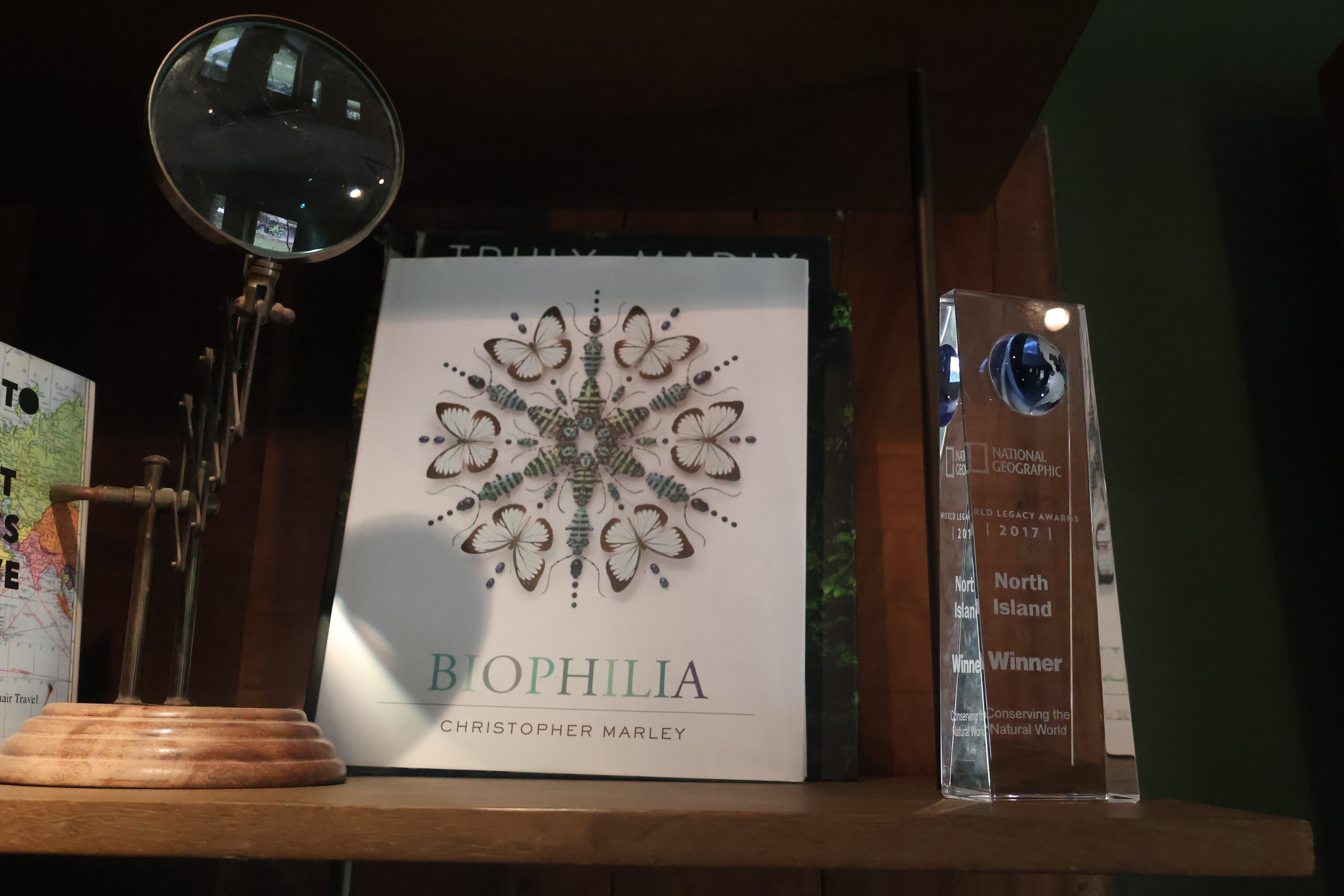

The Noah’s Ark Project has received international recognition for its approach to conservation and environmental stewardship, including the National Geographic Traveler World Legacy Award for Conserving the Natural World. This award recognises North Island’s sustained commitment to biodiversity restoration, responsible land management, and long-term ecological monitoring. Importantly, the recognition reflects the project’s integrated, evidence-based approach rather than short-term environmental outcomes or single-species interventions (North Island, 2025).

At the core of the Noah’s Ark Project is the understanding that island ecosystems function as tightly linked systems. Changes in vegetation structure, soil stability, or freshwater availability can influence habitat quality across the island and affect species ranging from terrestrial reptiles and birds to freshwater fauna. Restoration efforts therefore focus on reinstating ecological processes at an island scale, including invasive species removal, rehabilitation of native vegetation communities, and the restoration of wetland systems (IUCN, 2020).

This whole-island approach is particularly important for endemic species conservation. Rather than managing species in isolation, the Noah’s Ark Project aims to create the habitat conditions necessary for endemic species to persist within a functioning ecosystem. Endemic species monitoring is embedded within this framework and is used to assess whether restored habitats are supporting ecological function over time.

Long-term monitoring plays a central role in the project. Data collected over multiple years allows conservation teams to observe trends, assess habitat recovery, and adapt management strategies as environmental conditions change. This emphasis on monitoring aligns with international best practice for ecosystem-based conservation and climate resilience in island systems (IPBES, 2019; IUCN, 2020).

Wildlife ACT supports the Noah’s Ark Project through its long-term involvement on North Island, contributing to the continuity of biodiversity monitoring and ethical conservation support. By working alongside the island’s Environmental Team, Wildlife ACT helps ensure that endemic species data is collected consistently and contributes to evidence-based conservation management within this award-winning restoration framework (Wildlife ACT, 2024).

Which Endemic Species Are Actively Monitored on North Island Seychelles

Endemic species monitoring on North Island Seychelles focuses on a suite of species that provide insight into ecosystem function across terrestrial, freshwater, and wetland habitats. These species have been selected for monitoring because they represent different ecological roles, habitat requirements, and sensitivities to environmental change. Together, they help conservation teams understand how restored habitats are functioning over time within the broader Noah’s Ark Project framework (North Island, 2025).

Monitoring multiple endemic species allows for a more comprehensive assessment of ecosystem health than relying on a single indicator. On small islands, ecological processes are closely linked, and changes in one habitat type can influence others. By tracking species associated with forests, wetlands, and freshwater systems, conservation teams can identify emerging pressures, habitat trends, and potential risks before they result in widespread degradation (IPBES, 2019).

On North Island, endemic species monitoring prioritises the Aldabra Giant Tortoise as a keystone species due to its ecological significance and the depth of long-term data available. This is complemented by monitoring of indicator species such as the Seychelles White-eye and Black Mud Terrapin, which provide information on habitat quality and freshwater system health. A broader group of endemic birds and reptiles is also recorded to understand overall biodiversity patterns within restored habitats.

This tiered monitoring approach reflects international best practice for island conservation, where long-lived keystone species, habitat indicators, and wider biodiversity assemblages are monitored together to build a robust understanding of ecosystem recovery and resilience (IUCN, 2020).

Wildlife ACT supports endemic species monitoring on North Island through its Seychelles Marine and Coastal Conservation programme by contributing to consistent field presence, data collection, and monitoring continuity. This support helps ensure that monitoring efforts remain sustained over time and that endemic species data contributes meaningfully to adaptive management under the award-winning Noah’s Ark Project (Wildlife ACT, 2024; North Island, 2025).

Which Endemic Species Are Actively Monitored on North Island Seychelles

Endemic species monitoring on North Island, Seychelles focuses on a suite of species that provide insight into ecosystem function across terrestrial, freshwater, and wetland habitats. These species have been selected for monitoring because they represent different ecological roles, habitat requirements, and sensitivities to environmental change. Together, they help conservation teams understand how restored habitats are functioning over time within the broader Noah’s Ark Project framework (North Island, 2025).

Monitoring multiple endemic species allows for a more comprehensive assessment of ecosystem health than relying on a single indicator. On small islands, ecological processes are closely linked, and changes in one habitat type can influence others. By tracking species associated with forests, wetlands, and freshwater systems, conservation teams can identify emerging pressures, habitat trends, and potential risks before they result in widespread degradation (IPBES, 2019).

On North Island, endemic species monitoring prioritises the Aldabra Giant Tortoise as a keystone species due to its ecological significance and the depth of long-term data available. This is complemented by monitoring of indicator species such as the Seychelles White-eye and Black Mud Terrapin, which provide information on habitat quality and freshwater system health. A broader group of endemic birds and reptiles is also recorded to understand overall biodiversity patterns within restored habitats.

This tiered monitoring approach reflects international best practice for island conservation, where long-lived keystone species, habitat indicators, and wider biodiversity assemblages are monitored together to build a robust understanding of ecosystem recovery and resilience (IUCN, 2020).

Wildlife ACT supports endemic species monitoring on North Island through its Seychelles Marine and Coastal Conservation programme by contributing to consistent field presence, data collection, and monitoring continuity. This support helps ensure that monitoring efforts remain sustained over time and that endemic species data contributes meaningfully to adaptive management under the award-winning Noah’s Ark Project (Wildlife ACT, 2024; North Island, 2025).

Aldabra Giant Tortoise as a Keystone Endemic Species in the Seychelles

The Aldabra Giant Tortoise is one of the most ecologically significant endemic species in the Seychelles and is widely recognised for its role as a keystone species in island ecosystems. Keystone species are organisms whose ecological influence is disproportionately large relative to their population size, meaning their presence or absence can strongly affect ecosystem structure and function (IUCN, 2020).

In island environments, large native herbivores such as giant tortoises have historically played important roles in shaping vegetation structure, influencing plant regeneration, and maintaining habitat heterogeneity. Through grazing, movement, and seed dispersal, Aldabra Giant Tortoises interact with plant communities and soil systems in ways that influence ecological processes at a landscape scale (Griffiths et al., 2010).

The ecological importance of Aldabra Giant Tortoises is particularly relevant in the Seychelles, where island ecosystems evolved in the presence of large herbivorous reptiles rather than mammals. In these systems, tortoises contribute to maintaining open vegetation structures, facilitating seed dispersal, and supporting ecological dynamics that differ from continental environments (Hansen et al., 2010).

On North Island Seychelles, Aldabra Giant Tortoises are present within a restored island ecosystem under the Noah’s Ark Project. Their role is understood within a long-term ecological context rather than as a short-term restoration tool. Conservation teams focus on observing how tortoises utilise rehabilitated habitats and how their behaviour aligns with broader ecosystem recovery, without attributing specific restoration outcomes directly to their activity.

This cautious, evidence-based framing is important for endemic species conservation. While global research demonstrates the ecosystem engineering potential of giant tortoises, outcomes vary depending on habitat condition, species composition, and historical land use. On North Island, the emphasis remains on long-term monitoring and ecological observation to build understanding over time (Griffiths et al., 2010; IUCN, 2020).

Wildlife ACT supports this approach by contributing to the monitoring of Aldabra Giant Tortoises on North Island through its Seychelles Marine and Coastal Conservation programme. By supporting consistent data collection and field presence alongside the island’s Environmental Team, Wildlife ACT helps ensure that the ecological role of this keystone endemic species is understood within the broader context of the award-winning Noah’s Ark Project (Wildlife ACT, 2024; North Island, 2025).

How Wildlife ACT Ecotourists Support Aldabra Giant Tortoise Monitoring on North Island

Long-term monitoring of Aldabra Giant Tortoises on North Island Seychelles relies on consistent field presence and structured data collection over extended periods. Because giant tortoises are long-lived and exhibit slow population change, meaningful ecological understanding depends on observations gathered across seasons and years rather than short-term surveys alone (IUCN, 2020).

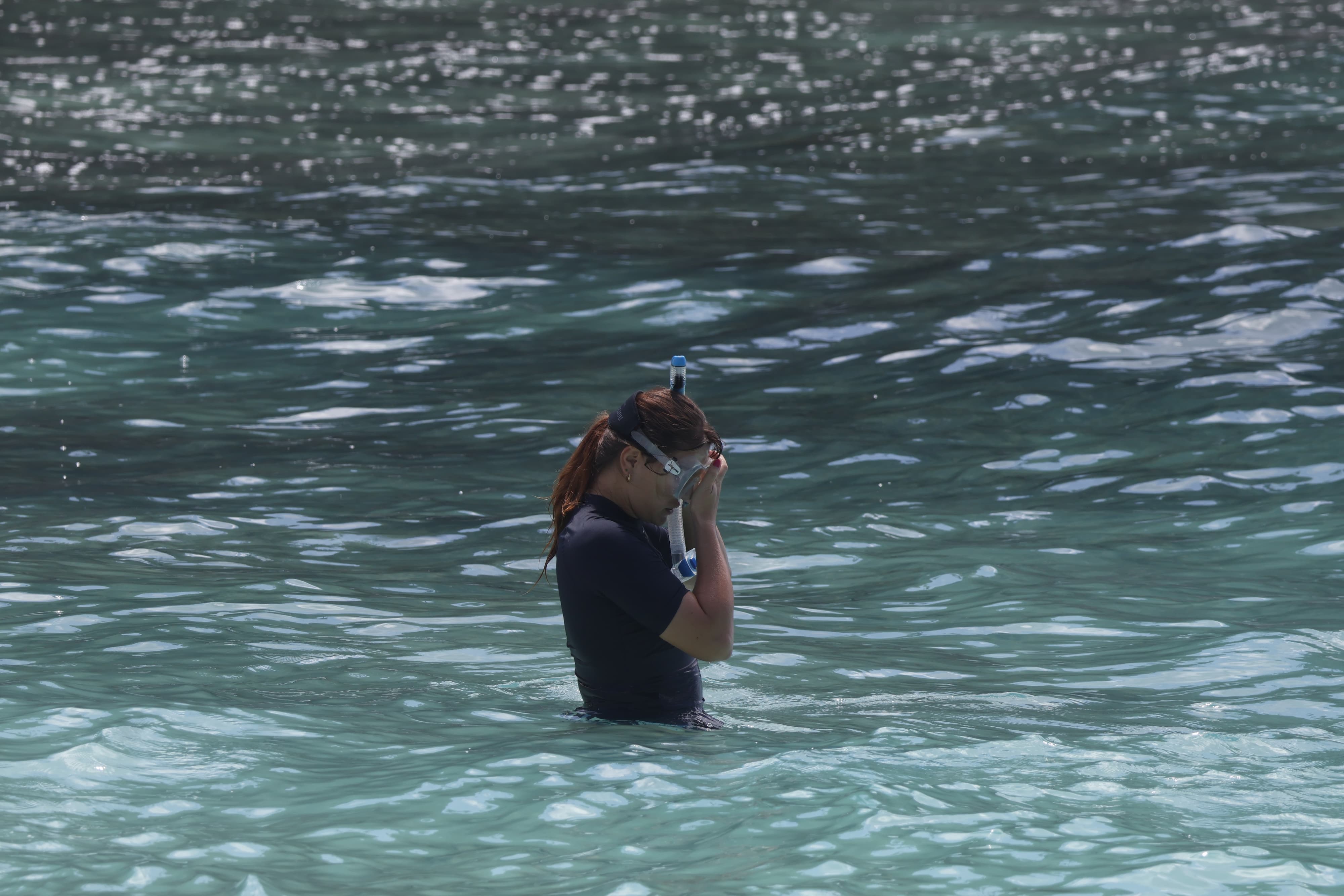

Wildlife ACT ecotourists play a defined and supervised role in supporting this monitoring as part of the organisation’s Seychelles Marine and Coastal Conservation programme. Working alongside North Island’s Environmental Team, ecotourists contribute to routine monitoring tasks that support population health assessments while operating within clearly established ethical and scientific protocols (Wildlife ACT, 2024).

Ecotourists assist with activities such as identifying individual Aldabra Giant Tortoises using microchip records, recording location data, observing behaviour and habitat use, and documenting nesting activity under supervision. These tasks contribute to long-term datasets that help conservation teams understand population structure, movement patterns, and habitat associations within the restored island ecosystem (North Island, 2025).

Ecotourists may also support the monitoring of hatchling emergence and juvenile tortoises within managed nursery systems, helping to record growth, health indicators, and survival during early life stages. All monitoring activities are overseen by professional conservation staff to ensure minimal disturbance and consistent data quality. Ecotourists do not design monitoring protocols or make management decisions, but support the continuity of field data collection that long-term conservation depends on (Wildlife ACT, 2024).

By supporting Aldabra Giant Tortoise monitoring in this way, Wildlife ACT ecotourists contribute to evidence-based conservation under the award-winning Noah’s Ark Project. Their role strengthens monitoring continuity on a remote island and helps ensure that data collected on this keystone endemic species contributes meaningfully to adaptive management and long-term ecosystem understanding on North Island (North Island, 2025).

Seychelles White-eye as an Indicator of Habitat Quality on North Island

The Seychelles White-eye is a small endemic bird species closely associated with native vegetation and intact forest structure. Because of its sensitivity to habitat condition, the presence and behaviour of the Seychelles White-eye provide valuable insight into vegetation quality, habitat connectivity, and ecosystem recovery on small islands (IUCN, 2022).

On North Island Seychelles, monitoring of the Seychelles White-eye is used as an indicator of terrestrial habitat quality within restored environments under the Noah’s Ark Project. Changes in distribution, frequency of sightings, and breeding behaviour help conservation teams understand how native vegetation rehabilitation supports endemic bird species over time (North Island, 2025).

Wildlife ACT ecotourists support Seychelles White-eye monitoring through structured observation and data recording alongside the island’s Environmental Team. Under supervision, ecotourists assist with bird surveys by recording sightings, habitat associations, and behavioural observations such as foraging and nesting activity. These observations contribute to long-term datasets that help track how bird populations respond to habitat restoration (Wildlife ACT, 2024).

Because the Seychelles White-eye relies on specific vegetation structure and food resources, its presence within restored habitats can reflect improvements in plant diversity and forest complexity. Monitoring this species alongside vegetation recovery provides a practical way to assess whether terrestrial restoration efforts are supporting broader ecosystem function rather than simply increasing plant cover (IPBES, 2019).

Long-term observation is essential for interpreting these indicators accurately. Short-term fluctuations in bird presence may reflect seasonal variation rather than habitat change. Wildlife ACT’s role in supporting consistent monitoring presence on North Island helps ensure that Seychelles White-eye data is interpreted within a long-term ecological context, contributing to evidence-based conservation management under the award-winning Noah’s Ark Project (Wildlife ACT, 2024; North Island, 2025).

Black Mud Terrapins and What They Reveal About Wetland Health on North Island

The Black Mud Terrapin is an endemic freshwater reptile in the Seychelles that is closely associated with wetlands, freshwater pools, and seasonally inundated habitats. Because freshwater systems on small islands are highly sensitive to environmental change, the presence and behaviour of Black Mud Terrapins provide important insight into wetland condition, water availability, and habitat connectivity (IUCN, 2022).

On North Island Seychelles, wetlands form a critical link between terrestrial and coastal ecosystems. Changes in rainfall patterns, vegetation cover, and soil structure can quickly affect freshwater availability and wetland function. Monitoring Black Mud Terrapins within these systems helps conservation teams understand whether restored wetlands are maintaining the ecological conditions required to support endemic freshwater species over time (UNEP, 2021).

Wildlife ACT ecotourists support Black Mud Terrapin monitoring as part of the organisation’s Seychelles Marine and Coastal Conservation programme. Working alongside North Island’s Environmental Team, ecotourists assist with structured wetland surveys that record terrapin presence, habitat use, and basic behavioural observations. These surveys are conducted under professional supervision and follow established protocols to minimise disturbance to both animals and sensitive wetland habitats (Wildlife ACT, 2024).

Because Black Mud Terrapins depend on stable freshwater conditions, their continued presence within restored wetlands can indicate effective water retention, suitable vegetation cover, and functional habitat connectivity. Monitoring results are interpreted alongside rainfall data, vegetation assessments, and broader biodiversity observations to build a holistic understanding of wetland health rather than relying on a single indicator (IPBES, 2019).

Long-term monitoring is particularly important for freshwater species in island environments, where seasonal variation and climate-driven changes can influence short-term observations. Wildlife ACT’s contribution to sustained field presence on North Island helps ensure that Black Mud Terrapin data is collected consistently over time and supports adaptive management within the award-winning Noah’s Ark Project (Wildlife ACT, 2024; North Island, 2025).

Other Endemic Species Supported by Habitat Restoration on North Island

In addition to the focal species monitored as part of structured conservation programmes, North Island Seychelles supports a range of other endemic species whose presence reflects broader habitat recovery under the Noah’s Ark Project. These species occupy different ecological niches and contribute to understanding overall ecosystem condition within restored terrestrial environments (North Island, 2025).

Endemic bird species such as the Seychelles Blue Pigeon and Seychelles Kestrel are associated with intact vegetation structure and habitat connectivity. Their continued presence on North Island provides insight into forest recovery, prey availability, and landscape-scale habitat function. While these species are not subject to intensive management interventions, routine observations contribute to broader biodiversity records and help conservation teams assess habitat suitability over time (IUCN, 2022).

North Island also supports endemic reptile species, including the Seychelles Small Day Gecko (Phelsuma astriata) and the Seychelles Skink. These species are closely linked to vegetation cover, microhabitat availability, and thermal conditions. Their distribution within restored habitats can reflect improvements in native vegetation structure and reduced pressure from invasive species, making them useful indicators of terrestrial habitat quality (North Island, 2025).

Monitoring of these species is integrated into broader habitat assessments rather than conducted as standalone programmes. Observations are recorded opportunistically during routine fieldwork and ecological surveys, contributing to long-term biodiversity datasets that support adaptive management under the Noah’s Ark Project.

Wildlife ACT ecotourists support this work by recording incidental sightings and habitat associations during supervised field activities. These observations help strengthen understanding of species distribution and habitat use without increasing disturbance or placing pressure on sensitive species. By contributing to this broader monitoring effort, Wildlife ACT helps reinforce a precautionary, ecosystem-based approach to endemic species conservation on North Island (Wildlife ACT, 2024).

Wildlife ACT’s Ethical Conservation Support Model on North Island Seychelles

Conservation work on remote islands requires long-term commitment, professional oversight, and clearly defined roles. On North Island Seychelles, endemic species conservation and habitat restoration are led by the island’s Environmental Team within the framework of the award-winning Noah’s Ark Project. Wildlife ACT’s role within this context is to provide ethical conservation support that strengthens monitoring continuity without directing or replacing professional management.

Wildlife ACT’s ethical conservation support model is built on role clarity and restraint. Ecotourists do not design conservation strategies, determine management actions, or conduct unsupervised research. Instead, they support established monitoring and data collection activities under professional supervision, contributing to the continuity of long-term datasets that island conservation depends on (Wildlife ACT, 2024).

This approach aligns with international best practice for responsible conservation engagement, which emphasises the importance of governance, scientific oversight, and minimising ecological disturbance. In sensitive island ecosystems, unmanaged or poorly structured participation can undermine conservation outcomes. Wildlife ACT’s model explicitly avoids this risk by embedding ecotourists within existing conservation frameworks rather than operating parallel or short-term projects (IUCN, 2020).

On North Island, this ethical support model enables consistent field presence across seasons and years. Long-term monitoring is particularly important for endemic species, where short-term observations rarely reflect meaningful ecological trends. By supporting routine data collection and habitat assessments, Wildlife ACT helps ensure that conservation decisions are informed by evidence rather than reaction, especially in the context of climate variability and gradual ecosystem recovery (IPBES, 2019).

The ethical conservation support model also prioritises minimal disturbance. Monitoring activities are designed to reduce stress on wildlife and avoid habitat degradation, with ecotourists trained to observe, record, and assist rather than intervene. This approach supports both data integrity and animal welfare, reinforcing the credibility of conservation outcomes under the Noah’s Ark Project (North Island, 2025).

By operating within clearly defined boundaries and supporting professional teams, Wildlife ACT contributes to a conservation model that values long-term stewardship over short-term impact. This model strengthens endemic species conservation on North Island by ensuring that habitat restoration and monitoring efforts remain evidence based, ethically grounded, and resilient over time.

Why Long-Term Stewardship Is Essential for Endemic Species Conservation on Islands

Endemic species conservation on small islands is inherently a long-term undertaking. Island ecosystems are shaped by slow ecological processes, limited species redundancy, and high sensitivity to environmental change. As a result, recovery following historical degradation does not occur quickly, and short-term interventions rarely provide meaningful insight into ecosystem stability or resilience (IPBES, 2019).

On islands such as North Island Seychelles, the persistence of endemic species depends on sustained habitat restoration, consistent monitoring, and adaptive management informed by evidence rather than short-term outcomes. Changes in vegetation structure, freshwater availability, and habitat connectivity unfold over years and decades, particularly in restored systems. Long-term stewardship allows conservation teams to distinguish between natural variability and meaningful ecological trends, which is essential for responsible decision-making (IUCN, 2020).

The Noah’s Ark Project provides the framework for this long-term approach on North Island. By focusing on whole-island restoration and embedding monitoring across terrestrial and freshwater habitats, the project supports ecosystem recovery at a scale appropriate to island systems. Endemic species monitoring within this framework is used to understand how restored habitats function over time, rather than to demonstrate rapid or isolated successes (North Island, 2025).

Wildlife ACT contributes to this long-term stewardship by supporting monitoring continuity and ethical conservation practice alongside North Island’s Environmental Team. Through its Seychelles Marine and Coastal Conservation programme, Wildlife ACT helps ensure that biodiversity data is collected consistently and interpreted within a long-term ecological context. This sustained presence is particularly important on remote islands, where logistical constraints can otherwise limit monitoring frequency and data continuity (Wildlife ACT, 2024).

Long-term stewardship also supports resilience in the face of environmental change. As climate variability increases pressure on island ecosystems, conservation strategies must be flexible and informed by ongoing observation. Endemic species that persist within restored habitats provide insight into ecosystem function under changing conditions, helping conservation teams adapt management approaches over time rather than reacting after degradation has occurred (IPBES, 2019).

By prioritising long-term stewardship over short-term outcomes, conservation efforts on North Island demonstrate how endemic species protection, habitat restoration, and ethical conservation support can work together to support ecosystem stability. This approach reflects the reality of island conservation, where meaningful outcomes are measured not in immediate results, but in the sustained capacity of ecosystems to function and support biodiversity over time.

Frequently Asked Questions

What endemic species can be found on North Island Seychelles

North Island supports a range of endemic species that reflect the recovery of terrestrial and freshwater habitats under the Noah’s Ark Project. These include the Aldabra Giant Tortoise, Seychelles White-eye, Black Mud Terrapin, Seychelles Blue Pigeon, Seychelles Kestrel, Seychelles Small Day Gecko (Phelsuma astriata), and Seychelles Skink. Together, these species occupy different ecological niches and provide insight into ecosystem function across restored habitats on the island (North Island, 2025; IUCN, 2022).

What endemic species can be found on North Island Seychelles

North Island supports a range of endemic species that reflect the recovery of terrestrial and freshwater habitats under the Noah’s Ark Project. These include the Aldabra Giant Tortoise, Seychelles White-eye, Black Mud Terrapin, Seychelles Blue Pigeon, Seychelles Kestrel, Seychelles Small Day Gecko (Phelsuma astriata), and Seychelles Skink. Together, these species occupy different ecological niches and provide insight into ecosystem function across restored habitats on the island (North Island, 2025; IUCN, 2022).

Why are endemic species important for island ecosystems

Endemic species often perform ecological roles that are highly specific to island environments. Because island ecosystems typically have limited species redundancy, the loss of an endemic species can disrupt key ecological processes such as vegetation regulation, seed dispersal, or freshwater system function. Protecting endemic species therefore helps maintain ecosystem stability and resilience, particularly on small islands where environmental change can have rapid, cascading effects (IPBES, 2019).

How does the Aldabra Giant Tortoise influence island ecosystems

The Aldabra Giant Tortoise is considered a keystone species in island ecosystems due to its influence on vegetation structure, seed dispersal, and habitat heterogeneity. In the Seychelles, giant tortoises evolved as primary herbivores and continue to interact with plant communities and soil systems within restored habitats. On North Island, their ecological role is studied through long-term monitoring rather than assumed outcomes (Griffiths et al., 2010; IUCN, 2020).

What role do Wildlife ACT ecotourists play in conservation on North Island

Wildlife ACT ecotourists support conservation on North Island by assisting with structured monitoring and data collection under the supervision of professional environmental teams. Ecotourists contribute to activities such as species observations, habitat assessments, and data recording. Their role is to support existing conservation programmes rather than direct management decisions, helping to strengthen long-term monitoring continuity within the Noah’s Ark Project (Wildlife ACT, 2024).

How does conservation on North Island contribute to broader biodiversity protection in the Seychelles

Conservation on North Island contributes to broader biodiversity protection in the Seychelles by restoring habitat, supporting endemic species persistence, and building long-term ecological datasets. Insights gained from island-scale restoration and monitoring help inform best practice for conservation across similar island systems within the Seychelles and other small island environments (North Island, 2025; IUCN, 2022).

How can someone become an ecotourist with Wildlife ACT in the Seychelles

To become an ecotourist with Wildlife ACT in the Seychelles, an individual must apply to join Wildlife ACT’s Seychelles Marine and Coastal Conservation programme on North Island. Applications are made directly through Wildlife ACT, where prospective ecotourists can review programme details, availability, and participation requirements before submitting an enquiry.

Once an enquiry is submitted, Wildlife ACT’s team provides further information on project timing, suitability, and next steps. Ecotourists are accepted into the programme based on availability and alignment with the project’s conservation objectives. Participation is structured and supervised, with ecotourists contributing to monitoring and data collection alongside North Island’s Environmental Team as part of the Noah’s Ark Project.

Before arrival, ecotourists receive guidance on programme expectations, ethical conduct, and the type of conservation support they will provide. On North Island, ecotourists operate within clearly defined roles and do not carry out independent research or management decisions. Their involvement is focused on supporting long-term monitoring and habitat assessments under professional supervision, ensuring that participation contributes meaningfully to conservation outcomes (Wildlife ACT, 2024).

References

Griffiths, C.J., Jones, C.G., Hansen, D.M., Puttoo, M., Tatayah, V., Müller, C.B. and Harris, S. (2010). The use of extant non-indigenous tortoises as a restoration tool to replace extinct ecosystem engineers. Restoration Ecology, 18(1), pp.1–7. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-100X.2009.00519.x (Accessed 9 February 2026).

Hansen, D.M., Kaiser, C.N. and Müller, C.B. (2010). Seed dispersal and establishment by giant tortoises in degraded island ecosystems. Biological Conservation, 143(12), pp.2731–2739. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2010.07.012 (Accessed 9 February 2026).

Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). (2019). Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Bonn: IPBES Secretariat. Available at: https://www.ipbes.net/global-assessment (Accessed 9 February 2026).

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). (2020). Guidelines for ecosystem-based approaches to climate change adaptation. Gland: IUCN. Available at: https://www.iucn.org/resources/publication/guidelines-ecosystem-based-approaches-climate-change-adaptation (Accessed 9 February 2026).

National Geographic. (n.d.). World Legacy Awards winners. National Geographic. Available at: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/worldlegacyawards/winners.html (Accessed 9 February 2026).

Wildlife ACT. (n.d.). A conservation adventure: Seychelles life as a North Island volunteer. Wildlife ACT Blog. Available at: https://www.wildlifeact.com/blog/a-conservation-adventure-seychelles-life-as-a-north-island-volunteer (Accessed 9 February 2026).

Wildlife ACT. (n.d.). Marine conservation volunteering in Seychelles. Wildlife ACT. Available at: https://www.wildlifeact.com/volunteer/program/marine-conservation-volunteering-seychelles (Accessed 9 February 2026).

Wildlife ACT. (n.d.). Restoring paradise: The Noah’s Ark Project and marine volunteering on North Island. Wildlife ACT Blog. Available at: https://www.wildlifeact.com/blog/restoring-paradise-the-noahs-ark-project-and-marine-volunteering-on-north-island (Accessed 9 February 2026).

Wildlife ACT. (n.d.). Volunteer in Seychelles. Wildlife ACT. Available at: https://www.wildlifeact.com/volunteer/seychelles (Accessed 9 February 2026).

.jpg)