An Introduction to Cheetah Conservation

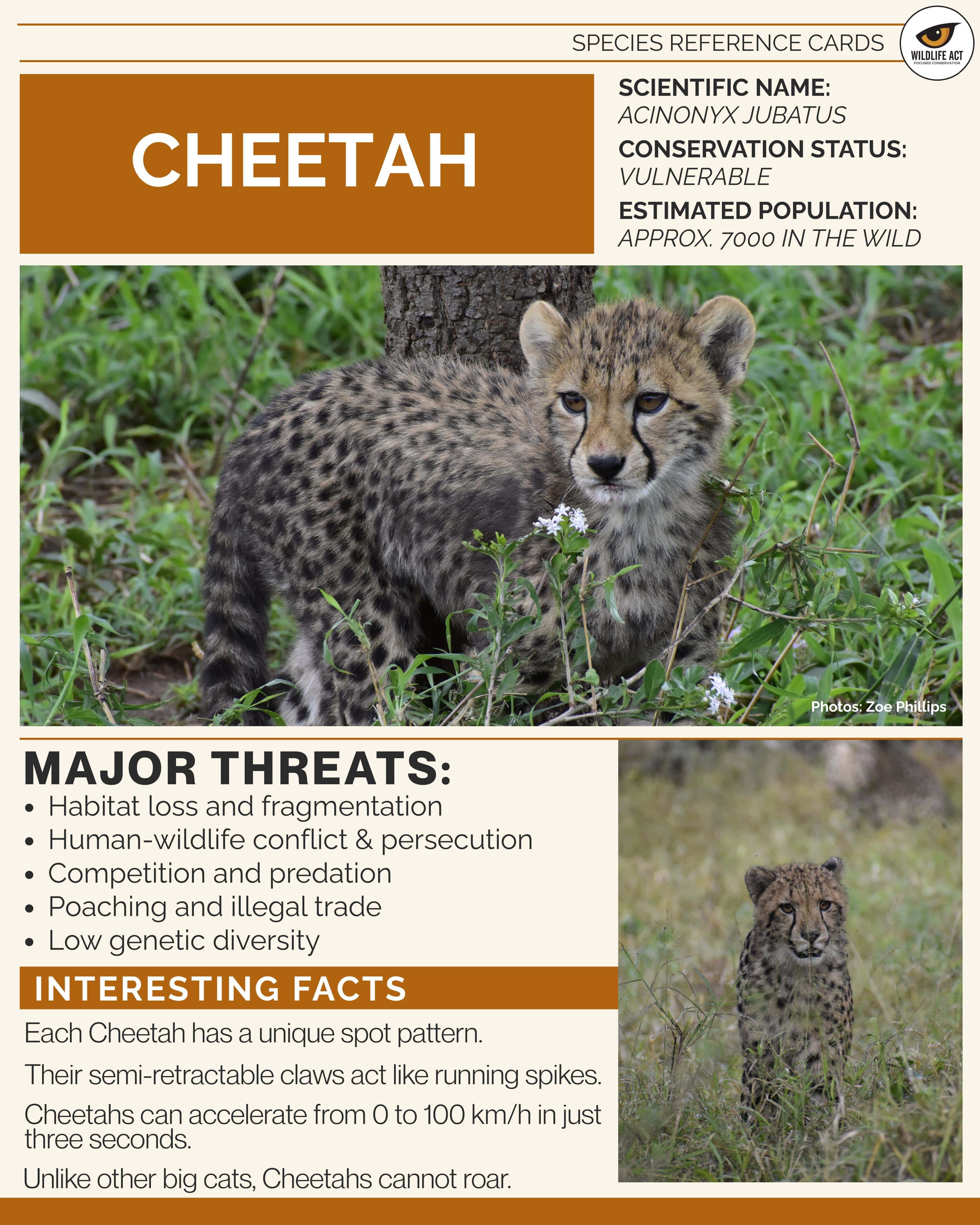

The Cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus), famed as the world’s fastest land animal, has long captured human interest with its speed and grace. Yet this iconic big cat is racing against time for its survival. Globally fewer than 7,000 Cheetahs remain in the wild, with roughly only about 1,000 individuals left in South Africa. Fragmented into isolated populations and under growing pressure, the Cheetah is classified as Vulnerable on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, which is just one step below Endangered.

In fact, some regional assessments consider the species even more at risk. Here in South Africa’s Zululand region (northern KwaZulu-Natal), where Wildlife ACT focuses its efforts, Cheetahs face intense challenges that threaten their future.

Wildlife ACT has made Cheetah conservation a central pillar of its work, combining science-driven monitoring, community engagement, and collaborative action to safeguard one of Africa’s most threatened large carnivores. By understanding why the Cheetah is a priority species and addressing the threats it faces, particularly in South Africa, we can better support initiatives to protect Cheetahs in South Africa and ensure this remarkable animal continues to thrive in the wild.

Understanding the IUCN Red List Status

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species is the world’s most comprehensive inventory of species’ conservation status. It categorizes species based on rigorous criteria, ranging from Least Concern and Near Threatened to Vulnerable, Endangered, Critically Endangered, and Extinct. A Vulnerable classification, such as that of the Cheetah, means a species faces a high risk of extinction in the medium-term future. In practical terms, this status signals ongoing declines and warns that without intervention, the Cheetah could slip into the Endangered category.

Wildlife ACT uses the IUCN Red List as a guiding framework to prioritize its efforts, focusing on species and populations (like the Cheetah) that are in urgent need of conservation action. In South Africa, where Cheetah numbers are low and pressures are high, the Vulnerable status underscores the importance of immediate, targeted measures to prevent further decline.

Cheetahs’ Need for Space and Safety

Cheetahs are uniquely adapted for speed, with slender bodies, long limbs, and flexible spines built for explosive acceleration. However, these adaptations come at a cost: Cheetahs are not built for conflict with larger predators and are often displaced by them.

They prefer expansive, open habitats like savannas and grasslands where they can use their keen eyesight and sprinting ability to hunt antelope and other prey. To maintain viable populations, Cheetahs require large, connected landscapes that allow them to roam, find mates, and avoid dangerous confrontations. In South Africa, most Cheetahs survive within fenced protected areas, which provide safety from human threats but also limit their natural movement. These conditions make habitat connectivity and careful management essential.

When habitats become fragmented or overcrowded with other big carnivores like Lions and Spotted Hyaenas, Cheetahs struggle and they may lose kills to competitors or suffer high cub mortality in areas with dense predator populations. This sensitivity to environment and competition means that the health of Cheetah populations is a strong indicator of overall habitat health and the effectiveness of conservation management. Simply put, if Cheetahs have the space and safety they need, it’s a sign that an ecosystem is being well managed.

Wildlife ACT supports Cheetah movement and genetic diversity through daily monitoring efforts and active participation in the national metapopulation strategy, which involves the managed movement of Cheetahs between fenced protected areas. While not directly involved in landscape-scale corridor creation, Wildlife ACT provides field-based data that helps inform decisions about where and when Cheetahs can be safely translocated, helping to mimic the ecological benefits of natural dispersal.

-min.jpg)

Key Threats to Cheetah Survival in South Africa

Multiple factors have contributed to the Cheetah’s decline, especially in South Africa. These “Acinonyx jubatus threats” are largely human-driven or exacerbated by human activities. Below are the major threats specific to South African Cheetahs and why they pose such a challenge:

- Habitat Loss and Fragmentation: The expansion of agriculture, human settlements, and roads has eaten away at the Cheetah’s range. Once ranging freely across the country, Cheetahs are now squeezed into smaller, isolated pockets of habitat. In South Africa’s Zululand, wild land is increasingly hemmed in by farms and development, fragmenting Cheetah habitat into disconnected islands. This limits the cats’ access to prey and prevents the natural movement of individuals between areas.

- Human-Wildlife Conflict: Although Cheetahs infrequently prey on livestock compared to other large predators, they are often blamed by farmers when livestock losses occur. Landowners may kill or persecute Cheetahs in retaliation or fear, viewing them as threats to cattle or game animals. To address this, Wildlife ACT’s Community Conservation Program works closely with local communities, helping implement better livestock protection, fostering understanding, and promoting non-lethal deterrents to predation. Building coexistence between people and predators is essential for long-term Cheetah survival in South Africa.

-Low Genetic Diversity: Cheetahs are famously genetically uniform – a result of historical population bottlenecks – and this is compounded by the realities of small reserve populations. In South Africa, most Cheetah groups are confined to fenced parks or private reserves, often just a few individuals in each. Without occasional introductions of new cats, inbreeding can occur, leading to lower birth rates and increased susceptibility to disease.

Low genetic diversity also reduces adaptability to environmental changes. Genetic isolation is thus a serious concern. Wildlife ACT and partners respond to this by moving Cheetahs between reserves (see metapopulation management below), essentially swapping animals to simulate natural gene flow. Careful monitoring identifies which cats are suitable to translocate to avoid inbreeding, ensuring the long-term genetic health of the metapopulation.

- Conflict with Other Predators: Cheetahs often lose out in the competitive hierarchy of large carnivores. Built for speed, not strength, they are no match for stronger predators like Lions, Spotted Hyaenas, or even Leopards. Cubs are especially vulnerable, with field data showing that predation is one of the leading causes of juvenile mortality. Wildlife ACT’s monitoring teams record these interactions to help inform predator management strategies, ensuring that conditions remain suitable for Priority species like the Cheetah to thrive.

Metapopulation Management in South Africa

One of the most important strategies for Cheetah conservation in South Africa is metapopulation management. This approach treats the numerous small Cheetah populations scattered in fenced protected areas as one larger interconnected population. By actively managing translocations, conservationists can ensure that no population becomes too inbred or stagnant.

In practical terms, metapopulation management involves identifying young adults that can be moved, finding suitable new homes for them in protected areas that need fresh genetics or have space, and then closely monitoring those animals post-release. It’s a complex operation requiring collaboration across many stakeholders.

In KwaZulu-Natal’s Zululand region, for example, Wildlife ACT works alongside Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife (the provincial conservation authority), the Endangered Wildlife Trust and other important stakeholders to facilitate these moves. Wildlife ACT helps track and monitor Cheetahs that are relocated, providing data on how well they adapt and integrate in the new environment. This includes observing their hunting success, territory establishment, and interactions with resident wildlife. If any issues arise (such as conflict with established predators or roaming toward unfenced boundaries), Wildlife ACT’s team can respond quickly as on-the-ground eyes and ears.

Thanks to this coordinated system, Southern Africa is now a regional stronghold for Cheetahs. Dozens of small reserves collectively host a growing Cheetah population that is managed as a meta-network. The metapopulation approach has prevented local extinctions and even allowed the reintroduction of Cheetahs into areas where they’d been wiped out decades ago. It’s a shining example of how scientific management can bolster a species’ prospects. South Africa’s Cheetah metapopulation has been steadily increasing in size and genetic diversity, offering hope that with continued effort, the Cheetah’s slide towards endangerment can be halted.

Volunteer Contributions to Cheetah Conservation

One of the most unique aspects of Wildlife ACT’s model is the integration of volunteers into critical conservation work. In Zululand’s monitoring projects, volunteers from around the world join the field teams and become an integral part of protecting Cheetah and other endangered and priority species. This is not a superficial voluntourism experience or safari; volunteers are treated as conservation partners and are given real responsibilities from day one.

Upon arrival, each volunteer goes through an intensive training and induction course. They learn how to use radio telemetry tracking equipment and GPS, how to orient themselves in the bush, and how to identify wildlife (including individual Cheetahs by their unique spot patterns). They’re taught to fill out data sheets properly and assist with setting up and checking camera traps. In essence, volunteers acquire the same skills that Wildlife ACT’s professional monitors use, ensuring they can contribute meaningfully to the work at hand.

Out in the field, volunteers help with daily tracking of Cheetahs that have been collared for monitoring. At predawn, the team piles into a 4x4 with a telemetry antenna, listening for the beeps that signal a Cheetah’s location. Once a Cheetah is located, the volunteers assist in observing its behavior (Is it hunting? Resting? Does it have cubs with it?), recording notes on its condition, kills, movements, and any interactions with other wildlife.

These observations feed directly into conservation decision-making. For example, if volunteers document that a Cheetah has been hanging around a perimeter fence and might be trying to escape or find new territory, the team can alert reserve management to keep an eye out or strengthen the fence in that section. If a Cheetah hasn’t moved from one spot in a while, volunteers might help investigate – it could be a large kill keeping it there, or there could be a snare injury preventing movement. In this way, volunteers act as extra eyes and hands on the ground, dramatically extending the capacity of Wildlife ACT’s monitoring program.

Beyond tracking, volunteers also contribute to camera trap maintenance, data management, and even interventions. Volunteers often help retrieve and sort these images, sometimes discovering new Cheetahs that were previously unknown in the area. In certain cases, volunteers may assist during animal darting or relocation operations, under the supervision of wildlife vets and officials.

Conclusion

The Cheetah’s legendary speed and elegance have earned it a place in our collective consciousness as a symbol of wild freedom. But speed alone cannot help this cat outrun extinction and it is up to us to remove the obstacles in its path. With fewer than 7,100 adult Cheetahs left globally and only a thousand or so in South Africa, the race to save them is truly on. We’ve seen that their decline is driven by habitat loss, human-wildlife conflict, genetic isolation, and illegal trade. Yet, as daunting as these challenges are, there is genuine hope.

Through concerted efforts like South Africa’s metapopulation management strategy, community-based conflict mitigation, and on-the-ground monitoring by organisations like Wildlife ACT, Cheetah numbers in certain reserves are stabilizing and even increasing. Each new cub born and reaching adulthood in Zululand’s protected areas is a small victory for the species.

Wildlife ACT works alongside dedicated partners, communities, and conservation authorities to help give the Cheetah a real chance at survival. The work being done across Zululand’s protected areas shows what is possible when people come together with a shared purpose. Whether you choose to volunteer, donate, or simply share the message, your support plays a role in protecting this remarkable species.

Cheetahs have evolved over millions of years to become one of nature’s most specialised hunters. Now, their future depends on the actions we take today. With continued effort, collaboration, and care, we can help ensure that Cheetahs remain a part of Africa’s wild landscapes for generations to come. That is why they remain a conservation priority, and why the work to protect them must continue.

References

- IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Acinonyx jubatus. (2024). Retrieved from https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/219/259025524

- Endangered Wildlife Trust. First Cheetah Swop of 2024 Marks Metapopulation Milestone. (2024). Retrieved from https://ewt.org/first-cheetah-swop/

- South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI). Cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) – Last National Assessment.(2016). Retrieved from https://speciesstatus.sanbi.org/assessment/last-assessment/1931/

- Wildlife ACT. Cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus). Retrieved from https://www.wildlifeact.com/about-wildlife-act/wildlife-species/cheetah-acinonyx-jubatus

Cover image by Jonathan Dutt